Zoe Zhang

Despite widespread ridicule, Turkey is persisting with reductions of its benchmark interest rates. While this may have contributed to the sharp declines in the exchange rates of the Turkish lira, it may prove to be a very sensible policy over time.

Turkey’s economy is in a tough spot: inflation is at double-digit rates; foreign exchange reserves are less than plentiful; and the corporate sector has to navigate a turbulent business environment.

But, when there are many competing policy objectives, it is crucial for the government to focus on the most important one. Turkey has chosen domestic production over and above exchange rates and I think that is a wise move.

In 1997-98, a more severe currency crisis raged through Thailand, South Korea and Indonesia, bankrupting countless businesses and making millions jobless. The three governments sought assistance from the International Monetary Fund. But the IMF imposed harsh “conditionalities” on its bailout funding, forcing these countries to raise interest rates and tighten fiscal expenditures.

However, instead of stemming capital flight, higher interest rates only caused a sharp contraction of economic activities and even more hardships. Only years later were the conditionalities relaxed and the three countries allowed more breathing space. There is now a consensus that the austerity in those years was counterproductive.

What we also learned through the crisis is that exchange rates are not the most important policy objective in a chaotic situation. During a time of uncertainty, you cannot expect to attract hot money inflows just because your interest rates are a few percentage points higher. And hot money is not helpful to your fundamental economy anyway.

Some policy analysts (myself included) argue that if a lower exchange rate is a nuisance enough, the government should consider imposing controls on capital flows rather than trying to lure hot money with stifling interest rates. No one likes currency controls, but it is a lesser evil than high interest rates.

To convince domestic residents to hang on to their lira savings, Turkey last week offered a compensation plan in the event of further lira depreciation. That may work well in the medium-to-long term. In 1988-92, China implemented a much bolder compensation programme for bank savers in the wake of double-digit inflation and a runaway currency crisis despite strict currency controls.

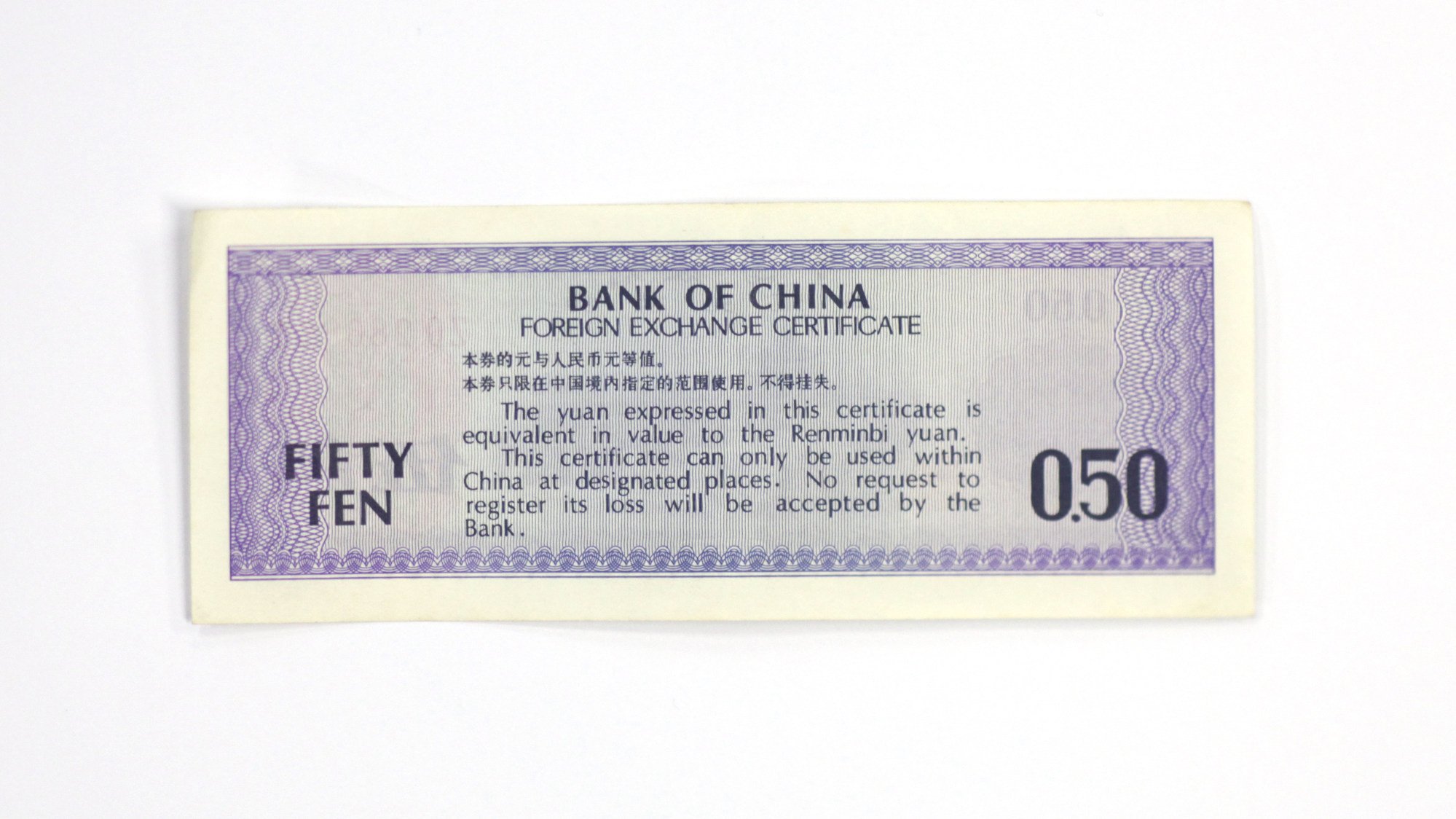

A grey market for foreign exchange had been rampant throughout the 1980s and 1990s, so much so that the central bank had to issue “foreign exchange certificates” to trade separately from, and in parallel to, the officially sanctioned foreign exchange market, and in recognition of street vendors who openly traded foreign currencies.

More relevant to the Turkish situation, China offered all household deposits (but not corporate deposits) that were longer than one year in maturity full compensation based on the monthly consumer price index. So, in some months, the compensation was more than 10 percentage points.

But still, the central bank always kept its lending rates stable, or unchanged at 6-8 per cent in those years, forcing credit rationing and worsening corruption. And the negative interest rate margin also became a huge burden on all state-owned banks.

Observers often make the mistake of focusing only on real interest rates. The reality is that nominal interest rates are also important. After all, business is conducted on nominal interest rates and borrowers pay nominal interest rates. When the benchmark interest rate stood at double-digit rates, Turkey’s corporate borrowers could not breathe, and rate cuts are only sensible.

If unintended consequences such as a lira decline (and imported inflation) can be mitigated somehow, that would be terrific. Otherwise, just ignore them. After all, expanding domestic production is the ultimate way to bring down inflation.

Source: South Chinan Morning Post