Hobbled by harsh US sanctions and a global economic downturn, Iran has discovered a new opportunity: hot air that carries messages to its opponents. China, albeit far less economically impaired, sees virtue in the business too.

A proposed 25-year humongous China-Iran cooperation deal has proven to be good business. Realms of media reporting and analysis and commentary by pundits serves to ensure that the two countries’ messages are delivered loud and clear.

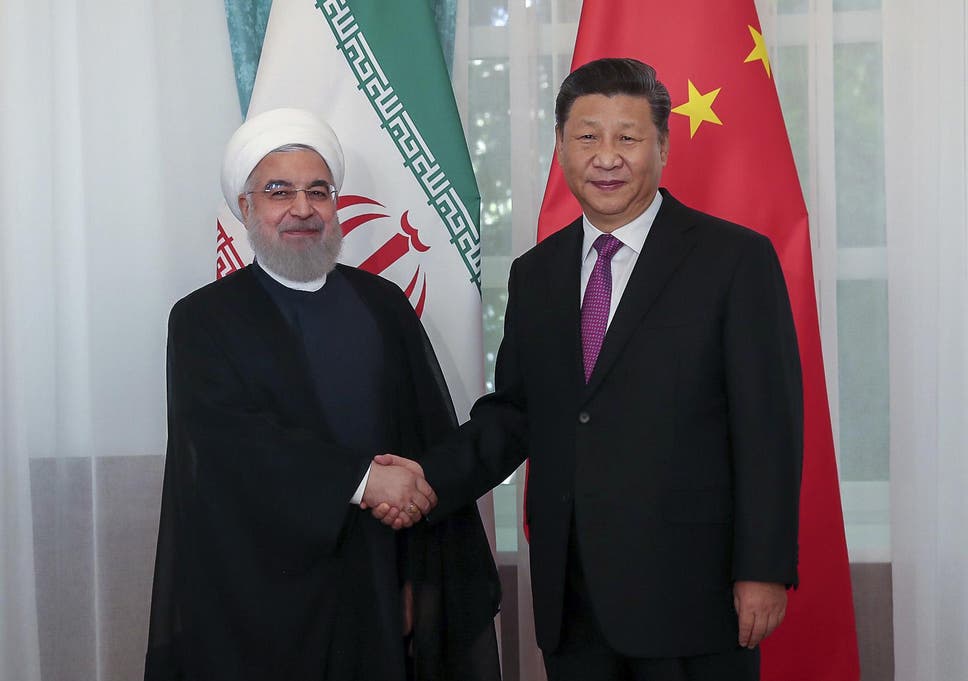

The two countries have provided the evidence to keep the story alive: Numerous agreements signed by Presidents Xi Jinping and Hassan Rouhani during the Chinese leader’s visit to the Middle East in 2016 would, if implemented, expand economic relations between the two countries by a factor of ten to $US600 billion and significantly enhance military cooperation.

The agreements, signalling a potential Chinese tilt towards Iran, were concluded at the time in anticipation of significant lifting of some and easing of other US sanctions as part of the 2015 international agreement that curbed Iran’s nuclear program.

Those hopes were dashed when US President Donald J. Trump pulled out of the agreement in 2018 and returned to the warpath with the introduction of crippling sanctions. China has since by and large abided by the US restrictions.

Iran appeared this month to put flesh on the skeleton with the leaking of a purported final draft of a sweeping 25-year partnership agreement that envisions up to US$400 billion in Chinese investment to develop Iran’s oil, gas, and transportation sectors.

The problem is that there is nothing final about the draft and that the draft constitutes little more than the floating of a trial balloon.

That is just fine as far as Tehran and Beijing are concerned even if both countries would likely opt to pursue cooperation on a far grander scale once geopolitical circumstances were more conducive.

For now, both countries have suggested that there is a long negotiation path to conclusion of an agreement, let alone implementation.

That does not mean that there is no upside to be had immediately.

By fuelling talk of an imminent agreement, Iran is signalling Europe and a potential Biden administration after the United States’ November presidential election that US and European policies threaten to drive the Islamic republic into the arms of China.

It also allowed Iran to take a swipe at Saudi Arabia, suggesting that when the chips are down it will be Iran rather than the kingdom that China turns to.

China capitalized on Iran’s hot air business by allowing it to flourish and boost messages Beijing was directing towards Washington and Riyadh.

Officially, China limited itself to a non-committal on-the-record reaction and low-key semi-official commentary.

Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian, a wolf warrior or exponent of China’s newly adopted more assertive and aggressive approach towards diplomacy, was exceptionally diplomatic in his comment.

“China and Iran enjoy traditional friendship, and the two sides have been in communication on the development of bilateral relations. We stand ready to work with Iran to steadily advance practical cooperation,” Mr. Zhao said.

Writing in the Shanghai Observer, a secondary Communist party newspaper, Middle East scholar Fan Hongda, argued that an agreement, though nowhere close to implementation, highlighted “an important moment of development” at a time that US–Chinese tensions allowed Beijing to pay less heed to American policies.

In saying so, Mr. Fan was echoing China’s warning that the United States was putting much at risk by retching up tensions between the world’s two largest economies and could push China to the point where it no longer regards the potential cost of countering US policy as too high.

China’s response also amplified its message to Gulf states echoed by scholars with close ties to the government that the People’s Republic’s interest in the Middle East was not a strategic priority.

These scholars suggest that the economic downturn, which impacts China’s economic ties to the region, could persuade Beijing to further limit its exposure if Gulf states failed to find a way to come to grips with Iran in way that would dial down tensions.

“For China, the Middle East is always on the very distant backburner of China’s strategic global strategies … Covid-19, combined with the oil price crisis, will dramatically change the Middle East. (This) will change China’s investment model in the Middle East,” said Niu Xinchun, director of Middle East studies at China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations (CICIR), widely viewed as China’s most influential think tank.

Iran this month, in an interesting twist that could indicate China’s appetite to play the Iranian card any time soon, dropped India as a partner in the development of a rail line from its Indian-backed deep-sea port of Chabahar because of delays in Indian funding. The Trump administration had exempted Chabahar from its sanctions regime.

Iranian Transport and Urban Development Minister Mohammad Eslami last week inaugurated the track-laying for the first 628 kilometres of the line that ultimately will link Chabahar to Afghanistan.

Iranian officials said Iran would fund the rail line itself but both China and Iran have repeatedly expressed in interest in linking Chabahar to Gwadar, the Chinese-backed Arabian Sea port, some 70 kilometres down the coast in Pakistan.

The economic downturn as a result of the coronavirus pandemic has revived doubts about the viability of Gwadar, a crown jewel of the approximately US$60 billion China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), China’s single largest Belt and Road-related investment.

In an indication that the United States does not see a potentially game-changing China-Iran deal as imminent, the Trump administration has so far stuck to reiterating its long-standing policy.

“The United States will continue to impose costs on Chinese companies that aid Iran, the world’s largest state sponsor of terrorism,” said a US State Department spokeswoman.