By Stijn Mitzer

After the recent success of Turkish unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs) in Central Asia, all eyes are now set on the profileration of Turkish drones in Africa. [1] Tunisia has ordered the Anka UAS by Turkish Aerospace Industries (TAI) while Morocco, Libya and Niger have all purchased Bayraktar TB2s. Other Sub-Saharan African countries like Angola, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Rwanda and Togo have either hinted at an acquisition of the TB2 or have already placed an order for the type. [2] More countries in Sub-Saharan Africa are almost certain to follow as the TB2 is arguably the first UCAV that manages to combine reliability and affordability with devastatingly effective results on the battlefield.

As analysts and drone buffs eagerly await any news of the next international TB2 sale, more countries are already lining up for the acquisition of Turkish drones in the meantime. In an

interview with SavunmaTR, the Indonesian ambassador to Turkey Dr. Lalu Muhammad Iqbal revealed that Indonesia is ”discussing the possibility of obtaining UAVs from Turkey” and that Indonesia hopes that ‘Turkey will not only supply UAVs, but also participate in the technology transfer and programmes for different UAV types in the future’, further adding that ”we are proud to see that Turkey is being talked about all over the world on this subject.” [3]

Relatively few countries in Southeast Asia presently possess an armed drone capability. Only Indonesia and Myanmar have so far acquired UCAVs, with Thailand and Vietnam currently in the process of developing indigenous armed drones. [4] [5] [6] Malaysia is set to acquire medium-altitude long-endurance (MALE) UAVs in the near future, and the Turkish TAI Anka currently appears to be the favoured candidate. [7] Malaysia isn’t yet pursuing an armed drone capability, although it doesn’t seem implausible that it will end up arming its MALE UAVs at some point in the future.

Indonesia for its part operates six CH-4B UCAVs acquired from China since 2019. This type fought off competition from the Wing Loong I and the Turkish Anka-S offered by TAI and PTDI. [8] Indonesia’s CH-4Bs can be are armed with air-to-ground missiles (AGMs) and have also been spotted with a communications relay or intelligence pod. [8] The country is also

pursuing a domestic UCAV programme run by PT Dirgantara Indonesia (PTDI). [9] Known as the Elang Hitam (Black Eagle), this programme is still several years away from spawning an operational system however. When it does enter service, it is destined to provide capabilities comparable to the CH-4B.

An interest in Turkish drones, almost certainly those designed by Baykar Tech, indicates that Indonesia is either eying additional UCAVs like the Bayraktar TB2 to supplement its CH-4Bs or drones that offer entirely novel capabilities (or both). Indonesia acquired its CH-4Bs with the initial aim of doctrine-building purposes and training crews on the use of MALE UCAVs, and it currently appears unlikely that more CH-4Bs will be acquired. [10] Especially the Bayraktar TB3, Akıncı and TAI Aksungur could offer novel capabilities to the Indonesian National Armed Forces (TNI).

|

Indonesia’s indigenous Elang Hitam UCAV.

|

Indonesia’s unique geographical nature whereby most of its population centers are separated by seas poses significant challenges towards the defence of the country. The TNI are responsible for patrolling an archipelago of 17,000 islands that extend 5,150 kilometers from east to west. For this purpose, it operates large numbers of patrol craft and maritime patrol aircraft to keep tabs on illegal entries and activies occuring within its territorial waters. As it happens, Dutch colonial forces were once faced with the same question of how to best patrol the immense archipelago.

During the late 1930s the Dutch grew increasingly concerned about the security of the Dutch East Indies, a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. Rather than building up a large naval force that would take at least a decade to design and construct, the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army Air Force instead came up with the aerial cruiser concept. [11] This concept called for the acquisition of large numbers of bomber aircraft and the construction of forward airstrips in every corner of the archipelago. In case of a Japanese invasion fleet nearing one of the Indonesian islands, large numbers of bombers could then be deployed to airstrips closer to the location of anger.

For this purpose, the Dutch East Indies acquired 121 Model 139WH and Model 166 bombers (export versions of the Martin B-10) from the United States. Although already dated by the time they entered service in the late 1930s, these were the only types that could readily be acquired. This fleet was later strengthened by bomb-toting Dornier Do-24 flying boats and Douglas Boston bombers, six of which reached the Dutch East Indies before it fell to Japan. [11] Although the old Martins were envisaged to be able to outrun and outgun Japanese fighters, their design parameters were soon overtaken by new Japanese fighter designs like the A6M Zero. Nonetheless, the Martins scored some notable victories and their acquisition was in essence the only viable option to mount a defence of the archipelago.

The aerial cruiser concept could perhaps be brought back to life to meet Indonesia’s modern defence requirements through the acquistion of the Bayraktar Akıncı, which’s 7,500km range and 24+-hour endurance is more than sufficient to cover each corner of the Indonesian archipelago while based at a centrally located air base. Airports located on other islands could support their operations by acting as forward arming and refuelling points (FARPs), ensuring each Akıncı is never long without fuel and munitions. The Akıncı also comes armed with a variety of standoff weapons, including 275+-km-ranged (anti-ship) cruise missiles and 100+-km-ranged beyond-visual-range air-to-air missile (BVRAAMs), allowing it to mount offensive operations against land, sea and (and to a limited degree) air targets.

|

Indonesia’s 100+ airports and air bases that are capable of supporting the operations of unmanned combat aerial vehicles.

|

The use of manned combat aircraft as aerial cruisers by Indonesia is hampered by their shorter endurance, a lack of (enough) tanker aircraft and their significant acquisition costs. The Indonesian Air Force (TNI-AU) currently operates a fleet of some 100 combat aircraft, including more than 30 F-16s and a dozen Su-30s. Other types include the Su-27, T-50, Hawk 200 and Embraer EMB 314 turboprop light attack aircraft. In February 2021, the Chief of Staff of the Indonesian Air Force revealed that the country intends to purchase the F-15EX and Dassault Rafale, likely putting an end to Indonesia’s earlier plans to acquire the Su-35. [12] Indonesia is also a partner in the KF-X fighter programme with South Korea, although an actual acquisition of the aircraft by the Indonesian Air Force is all but certain. [13]

Used alongside this exotic inventory of combat aircraft are a number of guided weapon types. The Su-30MKIs can deploy Kh-31P anti-radiation missiles, Kh-59M and Kh-29TE TV-guided AGMs, the F-16s can be armed with up to 100 JDAM guided bombs acquired in 2019 and AGM-65 AGMs, which also arm the T-50 and Hawk 200. Indonesia’s CH-4Bs use AR-1 and AR-2 AGMs. All but the AR-1/2 and AGM-65s are relatively poorly suited to provide effective fire-support to ground forces, forcing the TNI-AU to fall back on the use of unguided rockets and a variety of dumb bombs. Although the Indonesian Army (TNI-AD) has recently acquired attack helicopters armed with ATGMs, these are still lacking in numbers, with only eight AH-64Es and seven Mi-24s currently available for use in the entire country.

|

An Indonesian Su-30MKI parked next to most of the weapon types that arm the type.

|

|

An F-16 with a full load of M117 dumb bombs.

|

Owing to Indonesia’s enormous size and the sheer number of islands, the potential for synergy with artillery and multiple rocket launchers (MRLs) is limited. Considering the lack of ground-based fire-support assets that is to be expected during most military operations around the archipelago, airpower is a critical factor in any battle to be fought by Indonesia. A platform that can carry a hefty payload over a long distance is thus a prized asset. The Akıncı features a total of nine hardpoints under its wings and fuselage. The latter is to carry the heaviest ordnance ever cleared for carriage on a UCAV, comprising the 900kg weighing HGK-84 and the 275+-km ranged SOM cruise missile.

What sets the Akıncı apart from other UCAVs is its future capability to carry air-to-air missiles (AAMs). The Akıncı’s AESA radar enables it to locate targets at great range, and then engage them with Sungur MANPADS, Bozdoğan IR-guided AAMs or 100+-km ranged Gökdoğan BVRAAMs. The armament suite of the Akıncı continues with an arsenal of precision-guided missiles and bombs that gives it long-range strike capabilities, while the carriage of more than 18 MAM-L munitions makes it an ideal asset for providing air support to ground forces. [14] The TAI Aksungur is similarly capable of carrying a host of Turkish-produced munitions over long distances, and is the second UCAV in the world that can be equipped with dispenser pods for sonobuoys for anti-submarine warfare (ASW) purposes. [15]

While a possible acquisition of the Akıncı or Aksungur provides the TNI with a long-range strike asset, the smaller Bayraktar TB2 (or the Anka, although this type previously lost out to the CH-4B in Indonesia’s UCAV competition) could meet an immediate requirement for additional UCAVs prior to the expected introduction of the Elang Hitam later this decade. The option to install satellite communitions (SATCOM) to the Bayraktar TB2 meanwhile means that its range is limited only by its 27-hour long endurance (when installed, otherwise it’s around 300km). [16]

Indonesia’s desire to acquire drones from Turkey could also see an interest in the Bayraktar TB3, which was designed as a heavier version of the TB2 that can also operate from aircraft carriers and landing helicopter docks (LHDs). The Indonesian Navy has already experimented with using the indigenous LSU-02 UAV from the helicopter deck of one of its Diponegoro-class corvettes. Although the LSU-02 could only take-off from the vessel and in no way represents an operational capability, the test clearly indicates that Indonesia is interested in operating shipborne fixed-wing UAVs.

The Indonesian Navy currently operates a fleet of seven landing platform docks (LPDs), three of which are outfitted as hospital ships. Most of the LPDs were constructed by state-owned shipbuilder PT PAL Indonesia, which acquired the license to construct the Makassar class in cooperation with Dae Sun Shipyard of South Korea. In June 2014 PT PAL signed a $92 million contract for the delivery of two LPDs to the Philippine Navy. [17] Although delivered without many of the systems considered standard on contemporary ships in Western nations, the low unit price of some $45m means that these ships are now actually financially attainable for countries like Indonesia and the Philippines.

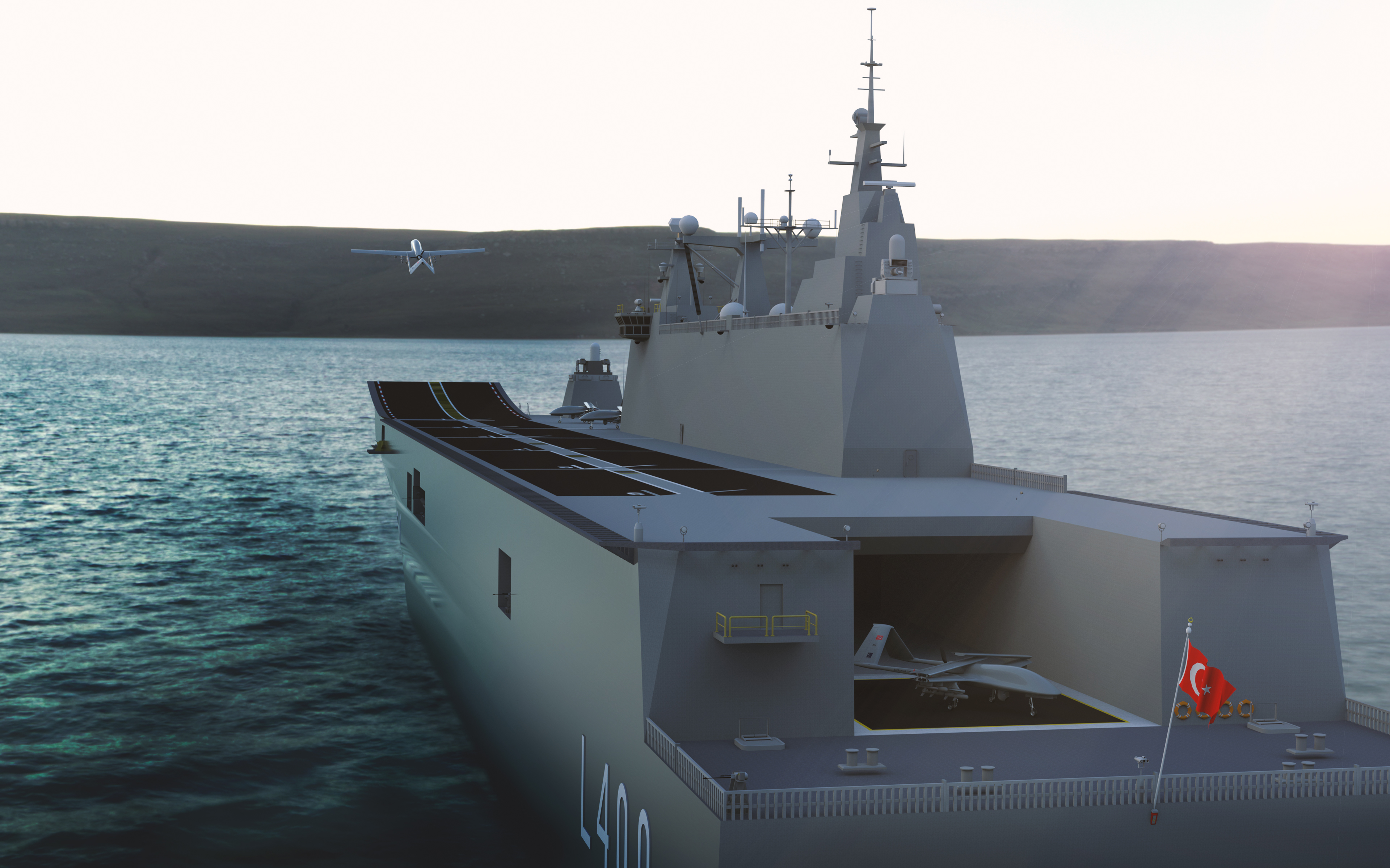

It is currently believed that the Indonesian Navy intends to procure several landing platform helicopter vessels (LPHs) in the coming decade. In 2018 PT PAL unveiled a 244-metres long LPH design that will likely form the basis of the design that will be offered to the Indonesian Navy. Similar to the Turkish TCG Anadolu LHD, the LPH design features a large aft elevator that can move helicopters and large U(C)AVs to the flight deck or hangar. Designed to be deployed from aircraft carriers and LPHs from the onset, the Bayraktar TB3 could be deployed from Indonesia’s LPHs with little design modifications required. Due to their small size and foldable wings, numerous TB3s could be deployed on the ships along with ASW helicopters and other drones to provide Indonesia with its first (unmanned-) aircraft carrier.

The TCG Anadolu LHD (and the follow-up vessel the TCG Trakya) are reportedly capable of carrying several dozen Bayraktar TB3s, a number that is only set to increase on the larger LPH design. [18] The Bayraktar TB3 can stay in the air for up to 24 hours while boasting a 280kg payload capacity. [19] This could either consist of up to six MAM munitions, including the MAM-T with a 30+km range, a maritime surveillance radar or a combination of both. This enables the TB3 to engage enemy naval vessels, support amphibious landings and carry out maritime surveillance. The expected low unit price of Indonesia’s LPHs (similar to its LPDs) in combination with the acquisition of TB3s could open up up entirely new possibilities for the Indonesian Navy.

|

PT PAL’s 244-metres long LPH design, which is some twelve metres longer than Turkey’s TCG Anadolu.

|

|

An artist rendering shows a Bayraktar TB3 taking off from the TCG Anadolu as another example is brought to the deck onboard the aft elevator.

|

The Indonesian ambassador to Turkey Dr. Lalu Muhammad Iqbal clearly voiced his country’s wish for Turkey ‘to also participate in the technology transfer and programmes for different UAV types in the future’. [3] In 2018 Turkish Aerospace Industries already partnered up with PTDI to offer the Anka-S for the Indonesian Air Force’s UCAV competition, in which the CH-4B was ultimately declared the winner. [20] Future collaboration could include a technology transfer along with the delivery of Turkish UCAVs that would benefit the final development phases of the indigenous Elang Hitam, with an assembly and maintenance center for Turkish UAVs in Indonesia and a joint UAV programme just some of the other possibilities.

The potential for military and technical cooperation between the two countries extends far beyond the UAV sector, with the

Kaplan MT/Harimau medium tank project developed jointly between FNSS and PT PINDAD arguably serving as the best example of what both countries can achieve when they join forces. [21] In late 2021 it was further revealed that negotations had begun on the procurement of warships from Turkey, while PTDI and TAI are already cooperating on the N-219 and N-245 turboprop passenger aircraft. [22] [23] With Turkey set to commence production of the

TOGG national electric car, its

indigenously-designed electric train and

electric tractors in 2022, technical cooperation could perhaps soon move beyond the military and aerospace sector as well. [24] [25] [26]

In 2012 Turkey was still actively trying to procure armed drones from the United States to meet its own needs. [27] Only ten years later the number of countries that have ordered Turkish UCAVs stands at twenty, sixteen of which have ordered UAVs from Baykar Tech. [28] Turkey has proved that a country doesn’t need to be a superpower with an unlimited R&D budget to accomplish impressive feats in the design of advanced technology. Whether Indonesia will acquire UAVs from Baykar or Turkish Aerospace Industries, it is certain that Turkish drones could end up playing a decisive role in Indonesian military capabilities.

[11] 40 jaar luchtvaart in Indië by Gerard Casius and Thijs Postma

Source: https://www.oryxspioenkop.com/2022/01/indonesia-eyes-turkish-drones-but-which.html