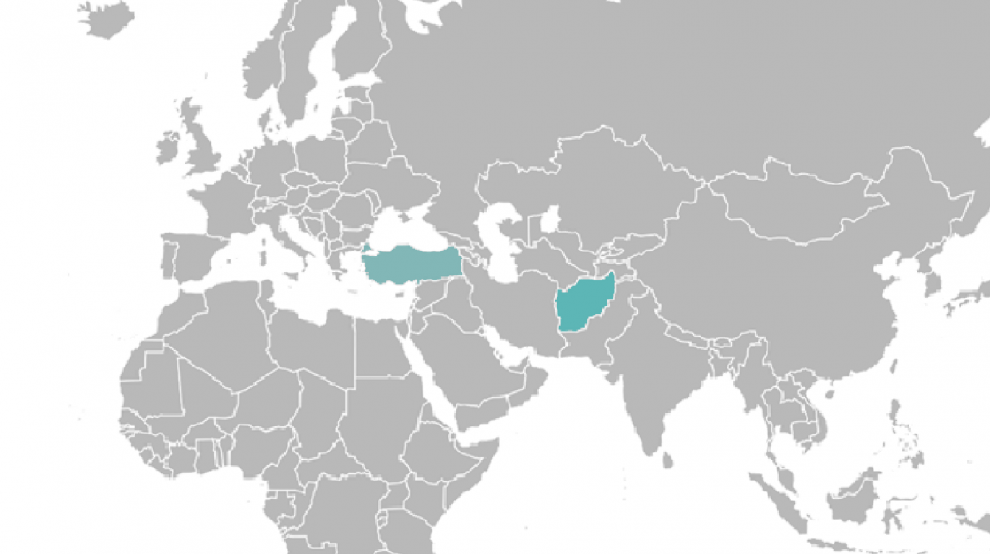

In recent weeks, there have been several statements from Turkish authorities, including the Turkish envoy to Kabul, affirming Ankara’s readiness to mediate between the various Afghan factions to reach an accord on the fate of the war-torn country.

On March 11, Turkey’s ambassador to Kabul Oğuzhan Ertuğrul told Anadolu Agency that Turkey is ready to host the intra-Afghan talks which were meant to follow the US-Taliban deal signed in Doha in late February. A more significant political role for Turkey in resolving the Afghan crisis may be appealing, not only to Afghans, but also to regional stakeholders.

In fact, Turkey may be uniquely qualified from among all the other contenders to serve as honest broker, with historic relations dating back at least a century and a measure of neutrality it overtly retains. By virtue of Ankara’s alliance with Qatar and Pakistan, Turkey has neither expressed a hostile position toward the Taliban, nor has it been particularly supportive of the Afghan government. In the midst of the current crisis in Afghanistan, the Afghan president has not made an official visit to Ankara since 2015, while opposition figures come in and out frequently, usually for “personal visits”.

Still, as outlined on the Turkish Foreign Ministry’s website, Ankara’s “policy towards Afghanistan is based on four pillars: maintenance of unity and integrity of Afghanistan; providing security and stability in the country; strengthening of broad based political structure in which popular participation is a priority and finally restoration of peace and prosperity by eliminating terrorism and extremism.”

This would not be the first time Ankara has stepped forward to serve as a neutral venue for intra-Afghan talks and to play a mediator role. A noteworthy previous attempt has been the Heart of Asia — Istanbul Process, which was initiated in 2011 to provide a platform to discuss regional issues and encourage security, political, and economic cooperation among Afghanistan and its neighbors.

To be sure, most Turkish officials admit, off the record, that Afghanistan is not a foreign policy priority for Turkey. It has much more pressing priorities with Syria, the US, the EU and the East Mediterranean. But Turkey does have significant investments in Afghanistan, even if the trade volume has fallen in the last couple of years. Some 127 Turkish companies still operate in Afghanistan, mainly in construction and contracting. And Turkey has troops on the ground as part of NATO. As the only Muslim nation in the NATO presence, it is generally agreed that the Turkish troops are regarded differently than the other foreign troops. They enjoy a special status; as fellow Muslims, the Turkish troops are not seen as “foreign invaders”.

On that note, as Donald Trump ploughs ahead with plans to withdraw from Afghanistan, in some quarters in Washington, DC, there is concern that the Asian playing field is being left wide open to Russia, Iran and China. A greater role played by Turkey, a natural player in the landscape, could be of use to the Americans to safeguard their interests.

Among Afghan leaders and the general population, Turkey enjoys a positive reputation, and this is in no small part due to historical bonds. The influence of the Turkish republic in Afghanistan goes back a century, to the days of Amanullah Khan in the early 1900s when the nascent Turkish republic, under Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, was seen as a model for progressive Muslim societies. Many of the reform policies adopted by Amanullah Khan were very much inspired by Ataturk’s Turkish republic. Also working along these lines was the king’s father in law, Mahmoud Tarzi, who came to be known as the father of Afghan journalism.

Amanullah’s consort, Queen Soraya, was a pioneer in women’s rights. With the help and support of Queen Soraya, several Afghan women were sent for higher education to Turkey in the late 1920s onward. In fact, a Turkish education remains prestigious for Afghan families until today.

There are also the ethnic links through the Uzbek minority in Afghanistan, and the special attention Turkey accords to Turkic people everywhere in the world.

Although Turkey’s influence may not be as palpable in Afghanistan as it may once have been, it has remained consistent over the years. Many Afghan military officers, for instance, have been trained by Turkey. And the Turkish troops present in Afghanistan today as part of the NATO mission enjoy a special status. As fellow Muslims, the Turkish troops are not seen as “foreign invaders”.

On a soft power level, since coming to power in 2002, the AK Party, under Recep Tayyip Erdogan, has made no secret of its ambitions to reclaim Turkey’s leadership role in the Muslim world. Turkey’s efforts on the humanitarian and education level across the Muslim world have contributed to its rising influence on a social and cultural level, namely the global success of its soap operas. War-weary Afghans have also tuned in to Turkish dramas which have proven to be culturally-appropriate alternatives to Bollywood’s song-and-dance escapism and Hollywood’s “America saves the world” propaganda.

Arguably, the idea of Turkey coming to the rescue may find a receptive audience in Afghanistan.

Add Comment